Ciseco ARF/XRF Range Test

Ever since I started using Ciseco XRF radio modules for wireless communication, I’ve been fascinated by the possibility to connect even remote corners of the house to the internet; areas where we have neither power sockets nor WiFi coverage. The theoretical range of the 868 MHz signal reaches into the kilometres under ideal conditions and using a setup with a directed antenna. In reality such distances are rarely ever achieved, as the radio signal is influenced (i.e. absorbed and/or reflected at varying degrees) by very much everything (anecdotally, ranges differ after rain as wet soil reflects radio better than dry soil). Thus, a distance of 2.2km between two successfully communicating XRFs even yielded a featured post on the Ciseco website last year. While the Ciseco web shop alludes to a “range expected to be 10′s Km’s” for ARF modules (ARF = “amplified” XRF) wired to an external antenna, in practice I had two XRF modules fail to communicate over a distance of less than ten metres through a relatively thin wall of our house. Range always depends! Nevertheless, the ARF carries an air of super power, and so I asked Miles from Ciseco if I could have some ARFs for a systematic comparison with the XRF.

While I’m personally quite interested to tease out the maximum distance between two ARFs using directed parabolic antennas between hill tops (one day…), **you won’t find any absolute range measurements here. **As I wrote previously, on a different day, under different weather conditions, in a different landscape, the maximum range of these modules is always going to be different and it would take a number of replicate measurements to establish the true limits of ARF-based radio communication. What I deemed more useful is the direct comparison between ARFs and XRFs, i.e. everyone with previous XRF experience can probably relate my results to their own setting.

Over the next few weeks I’m planning to test pairs of ARF<->ARF, ARF<->XRF and XRF<->XRF in different scenarios. While I had a temporary setup that tested reach in an urban setting (see my related blog post about dynamic GPS coordinate plotting, my first systematic test looked at signal strength in an open place with a few trees.

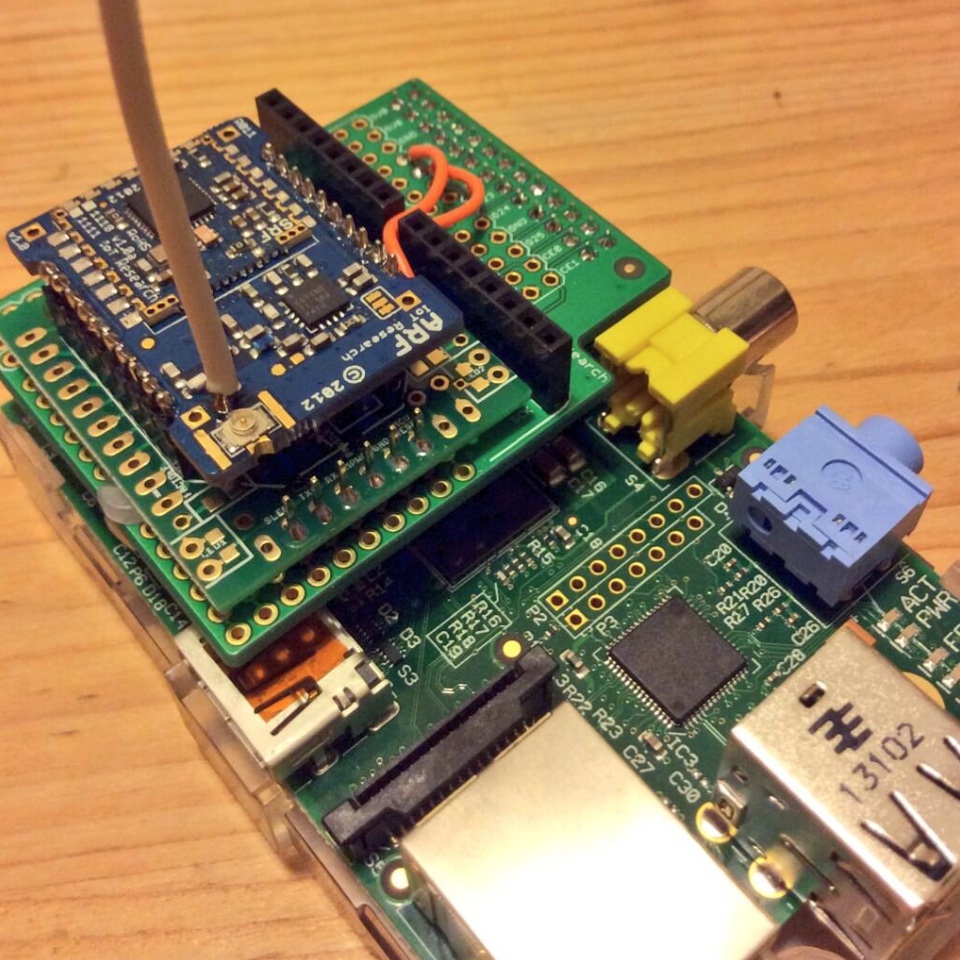

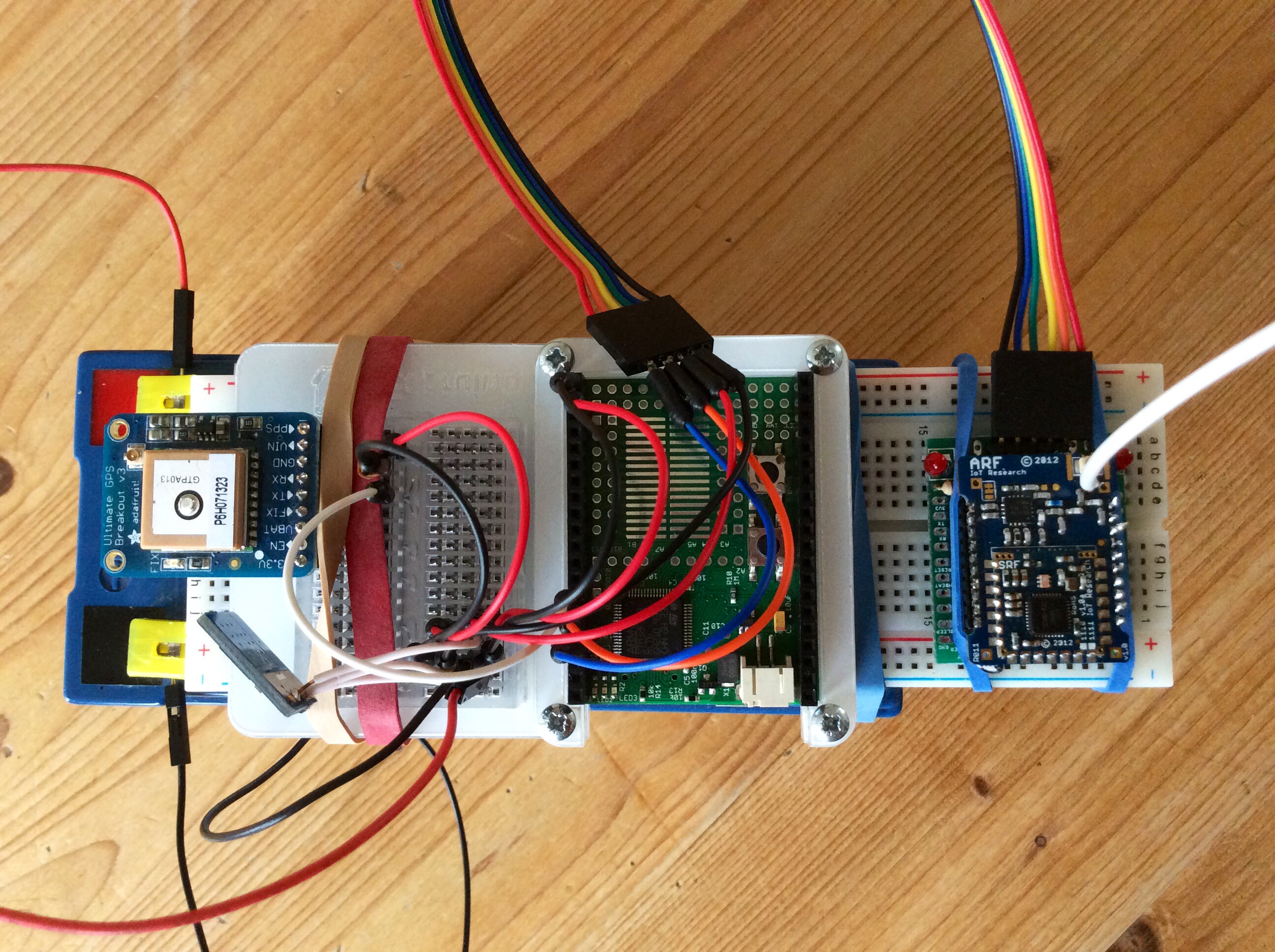

The experiment saw “the Big Mac of the IoT” (image in the top left, a Raspberry Pi with a passive XBBO on a Slice of POD to support the radio module with up to 350 mA) mounted at 150 cm at a fixed coordinate at the Cambridge Nightingale Recreation Ground. This device was configured as Slave. Another device, my mobile handset and Master (image to the left), was based on an Espruino JavaScript-based microcontroller, reading radio signals every second and saving signal strength and GPS coordinates to file. The Slave device was powered with a mobile USB juice pack (800 mA) and for this test, for the Master I opted for a nondescript 12 V UPS 12 Ah beast of a battery with a 3V3 1117 PowerPod because my GPS dropped out whenever I used my 500 mA Liquidware Lithium Backpack (at 5V with a 3V3 PowerPod). The Master and Slave terminology refers to the configuration of the radio modules in a signal strength measurement mode, and I configured an ARF as Master, an ARF as Slave, a XRF as Master and a XRF as Slave. All tests were run with the standard wire whip at 9600 bps.

In brief, every second the Master will send a packet to the Slave. The Slave will measure the incoming signal (in db)Â and send the packet straight back. The Master then measures the RSSI of the incoming and outputs something along the lines of: aSSRSSIS-045aMMRSSIM-046. This reads: The signal strength received at the Slave was -45 db, and the Master measured -46 dB coming from the Slave. In our experiment, I turned a round in the park and every second the Espruino (with my Master) recorded a line such as: aSSRSSIS-026aMMRSSIM-028 09:51:56 52.1777167 0.1495600 6 34.5 (that’s the RSSI messages, the time of taking the reading, the latitude and longitude of the measurement, the number of satellites contributing to the fix, and the altitude (usually quite inaccurate)). While very good RSSI values are in the range of -10 db to -20 db, Ciseco say that when “the RSSI figures reach -88 to -92 [db] you’ve reached the maximum distance you can achieve reliably”.

I tested: ARF(Master) vs ARF(Slave), ARF(Master) vs XRF(Slave) and XRF(Master) vs XRF(Slave). A somewhat cleaned yet raw version (lines without GPS fix removed) of my trip is available here: 3330 measurements, experiments separated at #####. I then split the dataset into Slave measurements (SS, signal coming from Master) and Master measurements (MM, signal coming from Slave).

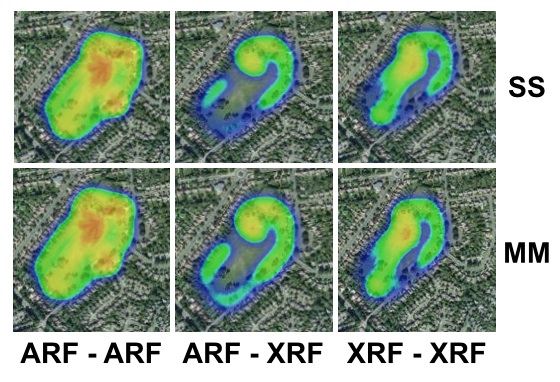

To get a visual representation of the data, I created a web page on the basis of heatmap.js see also on Github that encodes my MM and SS RSSI values as colour tone on a Google Map. Unfortunately, the heatmap library is not quite perfect yet, so if the data disappears from the view, zooming out one step usually fixes the problem. Here are three maps for the MM values:

The bright green spot in the ARF vs ARF measurements is our ground zero. In principle one can see the trajectories of my survey walks as shades of blue, although for technical reasons a few of the weaker signal strengths are not perfectly rendered for the ARF vs XRF and XRF vs XRF comparisons. A birds eye view over the area best shows the differences in signal strength around the park.

Note that I didn’t do one particular tour (the prominent line from ground zero towards 7 o’clock) for the ARF vs XRF combination, which no makes it appear as if there was no signal to be detected. (I should have done that one, arrrgh). However, what becomes clear is that overall the ARF vs ARF combination is significantly more powerful.

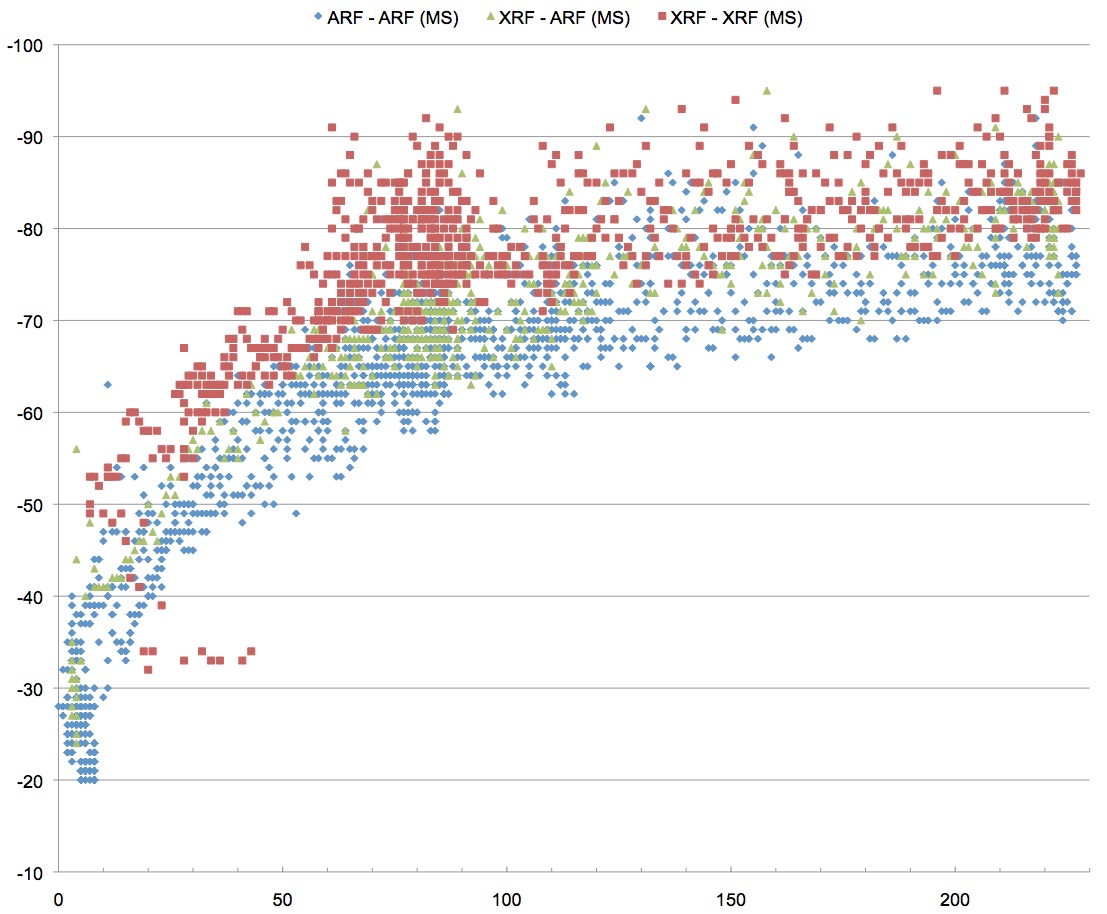

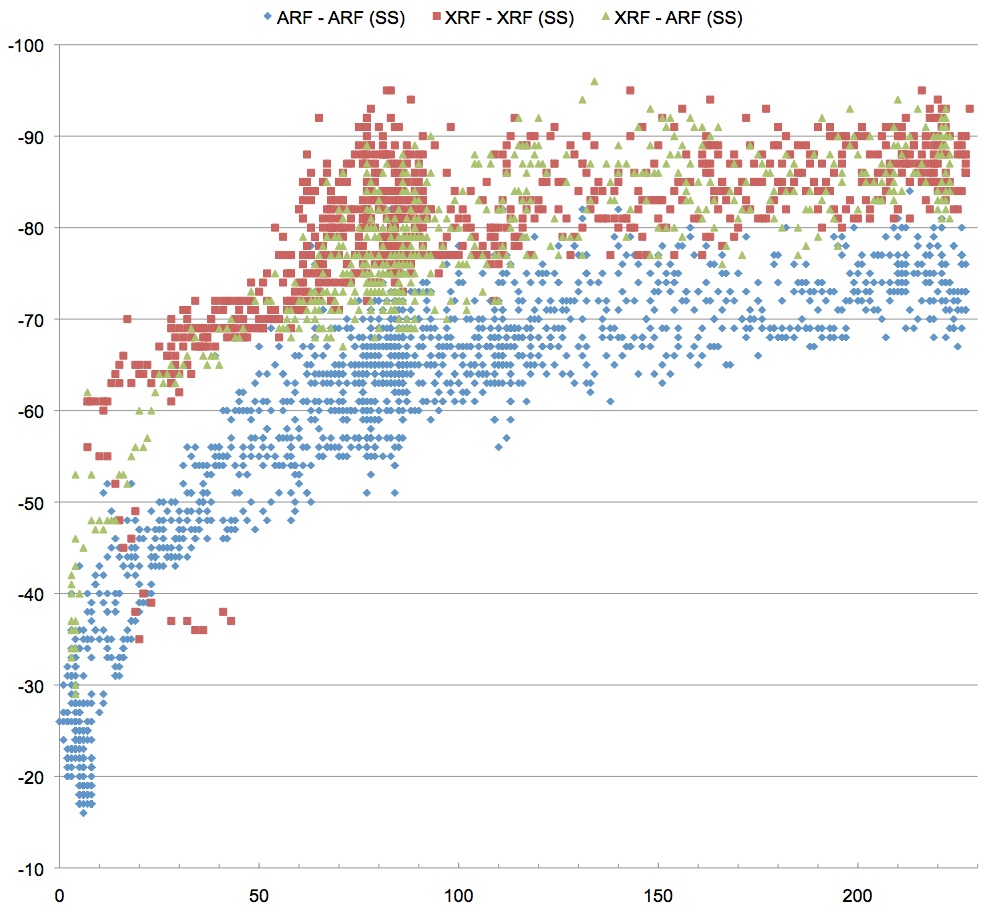

To quantitate how much more powerful the ARF signal is, I calculated the distance of each GPS coordinate to our ground zero (in metres) and plotted the signal strength (in db, closer to 0 is “better”) against it:

So what becomes clear is that even at shorter distances, the XRF seems to occasionally struggle if trees or people are in the way, whereas most data points for the ARF are below the -90 db level and suggest that we could increase the distance > 250m and still communicate comfortable. The much better db values for the ARF even for distances < 50m suggest that they may have more power for penetration of walls when used in a home setting.