Is it all machine learning?

Recently I engaged with James Baker, another Software Sustainability Institute Fellow and historian, in some friendly Twitter banter over the use of the phrase ‘machine learning’. As an individual with a background in the humanities as well as a thorough grounding in many technical aspects of modern life, James tripped over an issue that many non-technical folk are likely to struggle with: The boundary between some basic programmatic decision making and machine learning.

Machine learning fail: phone thinks I am in Caracas. I am not.

— James Baker (@j_w_baker) October 17, 2015

@BorisAdryan I guess it is one of those phrases the usage of which will gradually detach from its meaning (much like 'deconstruction').

— James Baker (@j_w_baker) October 17, 2015

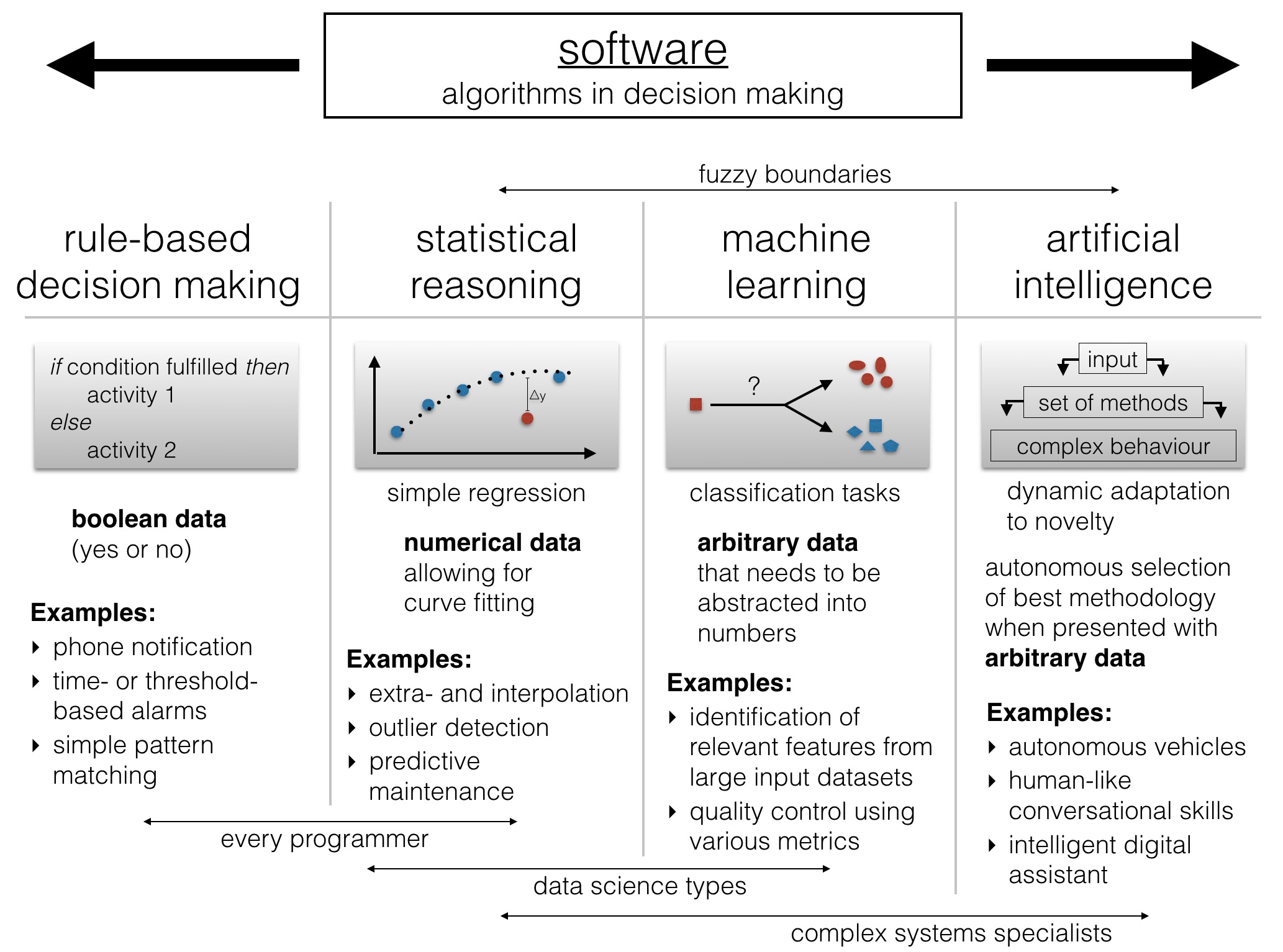

In a time when more and more tasks are assisted by software and computing is becoming increasingly ubiquitous (yep, I mean both your phone and the connected light bulb aka “Internet of Things”), I believe we need to differentiate between the following algorithmic entities:

First of all, we need to get away from big data as a term. What counts as ‘big’ changes from one year to the other, and the relevant question really is ‘how much is enough data to solve my problem?’. While for some rule-based decision making a single bit is sufficient information, statistical approaches intrinsically benefit from larger amounts of data. Of course this has an influence on where you can execute your decision making logic. Quite a few statistical/machine learning methods require the presence of many data points in memory, and those are less likely to be used in your mobile phone any time soon than they’re probably behind the decision making process in a cloud-based application. Think recommender systems on Netflix or Amazon.

Another frequently encountered term is data science. That leads me to the people who are most likely having the qualification to cleanly execute a decision making task in software. Everyone who calls themselves a serious programmer knows how to deal with numerical data. It doesn’t require much mathematical genius to implement a few methods for the inter- and extrapolation of numerical data, provided there’s a simple ‘input => output’ function that describes the observations. Remember that even MS Excel has functions to fit polynomials up to 6th or 7th order. Once you have established what output should follow which input, it is already possible to perform outlier detection or predictive maintenance – without diving much deeper into machine learning.

It’s hard to define what precisely constitutes data science and how it differs from basic mathematical reasoning. The boundaries are fuzzy. Curve fitting methods are secondary school material, while more advanced machine learning methods require a solid foundation in probabilistic thinking and the ability to integrate often vastly heterogenous data sources (both conceptually and by means of a programming language). If the decision making is based on simple data tuples and this data is sufficient for reliable decision making, for the sake of the argument, machine vibration vs failure rate, we can easily predict how much longer our turbine is going to run until it’s definitely going to fail. That’s not machine learning. However, life is often more complicated and machine failure might be a multi-factor problem. If we are presented with a large table containing all sorts of information, relevant or irrelevant (which we don’t know!), such as machine age, batch number, colour, maximum vibration, turbine diameter and blade angle, we can use unsupervised (explorative) and supervised (classification) machine learning methods to come up with a complex mathematical descriptor that helps use to predict when our machine is likely going to fail. Another term that’s lately seen a lot of hype is deep learning. While its proponents emphasise it as necessary step towards artificial intelligence, at its very core it’s just the extension of a set of conventional machine learning methods called neural networks, in which software mimics the interconnection and interaction of neurons in a simple brain.

What is real artificial intelligence? In a recent TechCrunch article Breaking The Barrier of Humans And Machines author Sudha Jamtje says “Machine learning and deep learning applied to smart things changes the human-machine interface. We are reaching an era of questioning what is artificial about AI. If human intelligence can be replicated, and human experience can be deep learned, the barrier between man and machine will begin to crumble.” That’s a rather philosophical view. On a more practical level, artificial intelligence describes software that dynamically choses the optimal combination of methods for the solution of a problem, often at very short temporal scales. One of the most beautiful examples of artificial intelligence can often be seen in robotics, as in this video of drones that cooperatively build a bridge:

Artificial Intelligence is not trivial and even seasoned data scientists are out of their depth here, I suppose. Good AI is developed by very specialised, highly interdisciplinary teams.