Four branches for an IoT ontology

The Internet Architecture Board is holding a workshop on Semantic Interoperability for the Internet of Things. They are seeking position papers and participants for their workshop in March. Unfortunately, standardisation is not a revenue generating operation for my company thingslearn and a two-day trip to San Jose is therefore out of the question. However, I’ve discussed a few thoughts with Michael Koster, who is one of the organisers and who is going to talk about his Machine Hypermedia Toolkit and the principle behind HATEOAS (Hypermedia As The Engine Of Application State).

In December 2014 I presented a talk on ontologies for the IoT at thingmonk London, an annual IoT conference organised by developer analyst company redmonk. During 2015 I refined my thoughts about the requirements for an IoT ontology and recorded a webcast with O’Reilly. I recycled that presentation a few times during 2015 and spoke about the lack of interoperability between devices in the consumer IoT also at the Data Science London Meetup as well as the Open Data Science Community. The decks for these are also available at Slideshare.

I used the IAB call for papers as incentive to finally writeup my ideas about an IoT ontology, although very brief:

Learning from Biology: A Four-Branch Ontology for The Internet of Things

Abstract

In this position paper we argue that ontologies and device annotation are essential resources to enable artificial intelligence and intelligent digital assistants for the Internet of Things. The biomedical research community has successfully established the Gene Ontology with the branches ‘Function’, ‘Process’ and ‘Localization’ to capture gene function. We propose that this tripartite framework is also suitable to define objects in the IoT, if it is complemented by a fourth sub-ontology that aims to capture human intuition: ‘Proxy and Avatar’. We conclude with organizational details and a recommendation for pragmatic choices in ontology design.

Introduction

In traditional machine-to-machine (M2M) communication there are usually well-defined workflows with concrete input, processing and output devices. An example for such M2M architecture would be an industrial control system with a set of sensors and actuators. However, in the emerging consumer Internet of Things (IoT), workflows will be dependent on each individual user, their interests, and their access to particular device combinations. Intelligent digital assistants will have to generate workflows dynamically and in real-time, based on user preferences and the capabilities of the available devices. A workflow for a user with an interest in home automation may control the heating system on the basis of room occupancy sensors, while a workflow for a user with an interest in health may depend on fitness and sleep tracking devices - and both workflows may require information from an outside thermometer.

For the purpose of this thesis, we assume that an intelligent assistant has access to a reliable device catalogue, i.e. it can obtain a truthful inventory of all IoT devices that are to the user’s disposition. However, in order to establish that there is a conceptual link between the outside thermometer and smart heating and/or exercise, the decision making process needs to explicitly know about this relationship (i.e. that thermometer X is an outside thermometer, and that the temperature suggests that going for a run is an appropriate activity). This information can be captured in an ontology, a controlled vocabulary with defined relationships between the entities. Unfortunately, there is no general and widely used ontology for the IoT yet, with semantic interoperability being one of many issues in ontology development.

Rather than enumerating the various shortcomings of current draft ontologies (e.g. W3C Semantic Sensor Network Ontology), and/or existing data, information and object models (e.g. IPSO Smart Objects, Eclipse Vorto), in this thesis we want to propose that one single-branched ontology cannot effectively represent complex relationships, but that a multibranch approach as it is used in the Gene Ontology (GO) can capture relevant computable meta-information: The ‘what’, ‘where’ and ‘when’ of device utility. Importantly, our approach does not replace the existing technologies, but allows for their integration through cross-references.

Learning from Gene Ontology

With the first complete genome sequences for eukaryotic organisms in the late 1990s, the computational biology community recognised the need for the systematic categorisation of gene function. The Gene Ontology Consortium agreed on three properties that are relevant to completely capture gene function:

- Function,

- Process,

- Localization.

Function describes the chemical activity that a gene exerts, Process provides the context in which this Function is required, and Localization where the gene is required to participate in the Process.

In the interest of brevity and scope the reader is referred to GO for biological examples. It suffices to say that GO is the defacto standard for biomedical functional annotation, with both academia and industry contributing to and using the resource heavily. At the time of writing, GO features over 40,000 unique *terms** in *three directed, acyclic graphs (reflecting the relationships ‘is a’,’part of’,’has part’ and ‘regulates’). They provide annotation from 100,000 scientific papers on more than 4 million genes across all phyla.

The Fourth Branch: Proxy/Avatar for

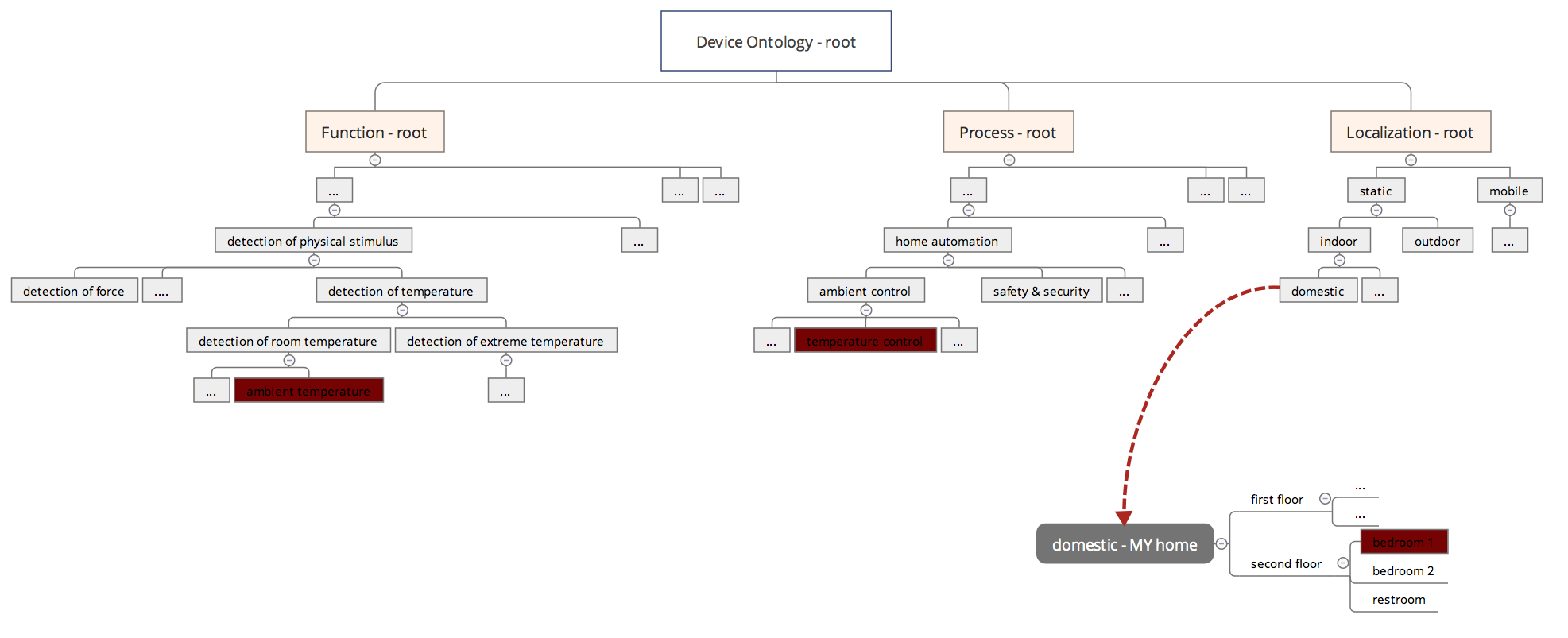

The three branches of GO are sufficient to provide a factual representation of an object, be it of biological nature or a device in the IoT. For example, a thermometer inside a smart thermostat can be trialled for it’s utility in a home automation workflow by looking at its most granular annotation: Function: ‘measurement of ambient temperature’, ‘directly interacts with a control unit’; Process: ‘domestic temperature control’; Localization: ‘bedroom 1’. (The user-specific term ‘bedroom 1’ is a result of overloading the generic IoT ontology term ‘domestic’, see Figure).

Figure: Annotation of a connected thermometer with the three sub-ontologies Function, Process and Localization. The term ‘domestic’ would allow the injection of a user-specific sub-ontology ‘MY home’. This operation would only affect the user’s active copy of the ontology, not the official version. The necessary reannotation of devices with ‘domestic’ localization would only be possible for those owned by the user.

Figure: Annotation of a connected thermometer with the three sub-ontologies Function, Process and Localization. The term ‘domestic’ would allow the injection of a user-specific sub-ontology ‘MY home’. This operation would only affect the user’s active copy of the ontology, not the official version. The necessary reannotation of devices with ‘domestic’ localization would only be possible for those owned by the user.

However, there is a meta-layer of information that is not as clear-cut and factual as Function, Process and Localization. It’s the the Proxy and Avatar function a device can have, and this is highly dependent on the individual user: Some cars are just cars, but your partner’s car in your driveway may be an indicator of their presence. The temperature sensor in your smart heating system can, under certain circumstances, be indicative of a fire. These are relationships that depend entirely on context and we anticipate a considerable amount of machine learning effort is going to be required to learn such context. The Proxy and Avatar sub-ontology would likely exist as a branch reflecting frequently inferred functions and processes, as well as a branch specific to the user which could be overloaded similar to the ‘domestic’ term in the example.

Ontology Building and Annotation Logistics

The Gene Ontology with its currently 40,000 terms has been built over the past 17 years, entirely by human curation. The US NIH has contributed $44,616,906 from 2001-2014, a sum likely matched by European funding bodies. This currently pays for 100 professional curators worldwide with domain-specific knowledge who continuously update and grow the ontology, and annotate novel biological entities. The curators use computational tools to manipulate both the ontology and the annotations, however, it is a manual process. As knowledge grows, ontology terms are frequently redefined, refined or retired. The necessary retrofit to the annotated genes is, again, manual, albeit with the support of appropriate automation tools. Even though subject of extensive machine learning efforts, automatic ontology building and gene annotation is widely considered experimental and not fit for production purposes.

The Open Biomedical Ontologies Foundry currently knows 50+ domain-specific ontologies. Where appropriate, GO terms carry optional cross-references to terms in those external ontologies. It is noteworthy that this mapping is usually the result of a manual process, as simple word-matching approaches have proven extremely unreliable.

Despite the size of the ontology, GO offers lightweight annotation with a few specific terms, as the relationship types allow the backwards-inference of less concrete terms; e.g. a “thermocouple transition joint probe” over multiple “is a” relationships indeed is a “thermometer”. However, the choice of ontology endpoint, degree of granularity and generality of terms has to be pragmatic. In one particular case, we established that the knowledge of 15 years of research yielded some 47 publications on a gene, which was work contributed by 100+ authors in 50+ PhD thesis. Nevertheless, the gene only has 15 direct annotations, giving rise to 150 inferred annotations.

When building an IoT ontology such pragmatism would allow the ontology to grow in small steps rather than exploding with each and every new device or device type. It would also allow community efforts and crowd-sourced activities for device annotation, as carefully balanced and more general terms are more easy to use (rather than vendor-specific fine-grained ones). Although there are going to be billions of connected devices in the future, many of these devices are going to be conceptually ‘the same’. Also, it is conceivable that the number of applications/workflows that users require is even smaller. It is therefore feasible to derive an ontology that caters well for all workflows without the need to annotate each device with the maximum number of fine-grained details. Certain meta-information as detailed in the Semantic Sensor Network Ontology (such as the survival range for a device), which is not relevant for the majority of workflows, would still be accessible through cross-references.

References

(in lieu of links in the document)

W3C Semantic Network Ontology [https://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/ssn/ssnx/ssn]

IPSO Smart Objects [http://www.ipso-alliance.org/ipso-community/resources/smart-objects-interoperability]

Eclipse Vorto [https://www.eclipse.org/vorto]

The Gene Ontology [http://geneontology.org]

The Open Biomedical Ontologies Foundry [http://obofoundry.org]

Organizing the Internet of Things - O’Reilly Webcast [http://www.oreilly.com/pub/e/3365]

Slides for: Organizing the Internet of Things [http://www.slideshare.net/BorisAdryan/oreilly-webcast-organizing-the-internet-of-things-actionable-insight-through-ontologies]

Slides for: Ontologies for the IoT - London Data Science Meetup, 28 May 2015 [http://www.slideshare.net/BorisAdryan/data-science-london-meetup-280515]