Hands-on with Vorto IoT information models

Last week I attended the Bosch Connected Experience (BCX) 2016, an event co-organised by the lovely Alex Deschamps-Sonsino and Peter Bihr for IoT practitioners during the otherwise suit-heavy Bosch Connected World week. It was a first of its kind and I was curious what could be done at a hack event that aimed to mix tinkerers, students and SME-type IoT specialists with Bosch engineers and their industrial kit. And yes, the Bosch PR machinery was full on, as you can tell by below video.

In a previous blog post I wrote about the use of ontologies in the IoT. An ontology establishes the relationships of objects to each other. The annotation of the objects, along with a link to an ontology, occurs in a data or information model for the object. This can be all rather abstract and subject to mostly academic research. However, a few implementations have lately emerged for the IoT, with the promise of greater interoperability between Internet-connected devices.

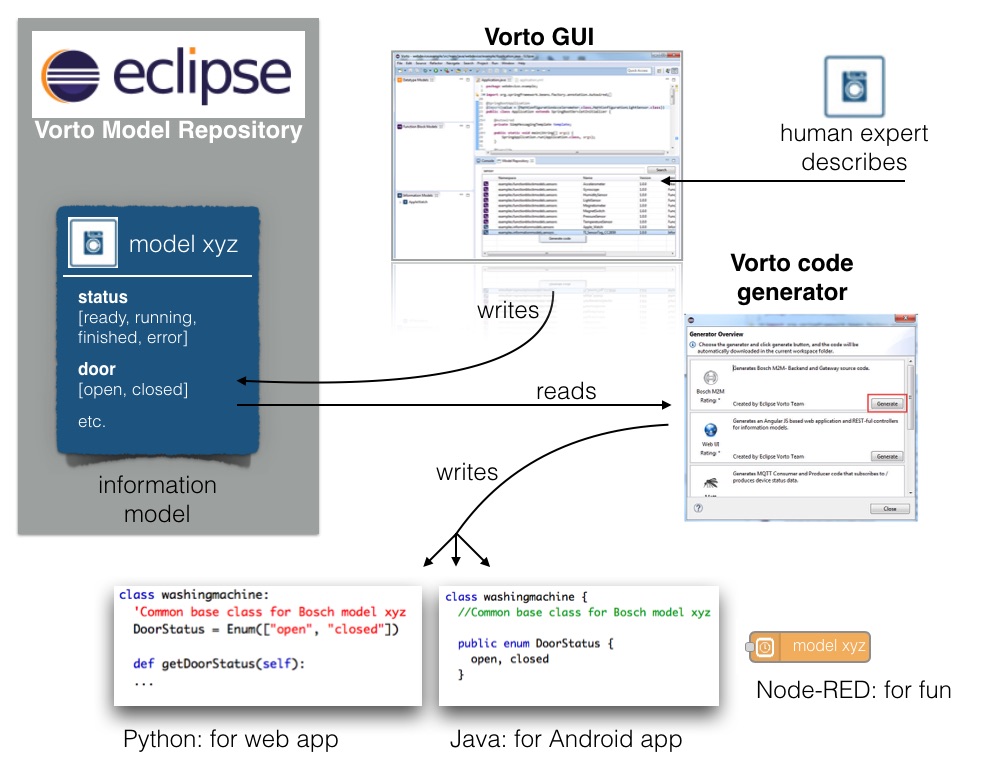

There’s been a massive push in the UK to annotate devices with the Hypercat standard, allowing the exposure of devices in a catalogue along with brief annotations of their function. Unfortunately, it is difficult to find Hypercat services “in the wild”, i.e. the adoption of the standard is rather restricted to those who have joined the consortium. Quite promising, however, is a new project: For the past year or so the Eclipse IoT project Vorto has been ongoing. It’s hosted by the Eclipse Foundation but provided with significant human resources by Bosch Software Innovations. Vorto is a graphical user interface for the definition of IoT information models (i.e. which data is associated with an Internet-connected device), but also comprises code generators for a range of programming languages that translate the model into ready-to-use code objects. In contrast to the Hypercat consortium, the Eclipse Foundation very early into the project made sharing an essential component of Vorto. There is now even a public repository of IoT data models, although the BCX event revealed that there are a lot more models finished and already being used at Bosch than they care to share publicly…

In brief, Vorto allows people to describe information models about their “thing” in a language-independent manner using the Vorto GUI. These models are then stored and made available in the Vorto repository. The Vorto code generator, an open design with a simple, extendable plugin-system, can take such an information model and convert it into a variety of different code representations, i.e. Python or Java classes. This has the big advantage that when adjustments to the data model are necessary, code changes are consistently translated to all languages. One example how Bosch uses the technology in-house is for the data (model) exchange with their cloud platform partner Thingworx. Bosch engineers define the data model for their products, Bosch software specialists use the model and the code to write applications, while the folk at Thingworx use a code generator specific to their platform. This way, both Bosch software and Thingworx implementation are guaranteed to match in terms of data model, minimising the effort to create complementary interfaces.

For the hack-a-thon, I chose to work on a project that would bring Vorto and my favourite rapid prototyping tool Node-RED together. As it is possible to query the Vorto model repository using a REST API, I had intended to write some JavaScript code that retrieves the model and on-the-fly converts it into a Node-RED node that can be deployed straight away. Unfortunately, I had completely neglected the fact that while it’s simple to define the interface, a Node-RED node without access to the actual hardware is rather pointless.

The Team, left to right: Nico, Christoph and Boris.

The Team, left to right: Nico, Christoph and Boris.

In the end, our team [Boris Adryan (web), Christoph Brockmann and Nico Castelli (web)] devised a strategy as follows: Using the official plugin system for code generators, we wrote a native Vorto plugin for Node-RED. On the way we’ve discovered a range of issues with undocumented dependencies and actual bugs, which we fed back to the Vorto team. With half of their staff being based in Singapore and their other half attending EclipseCon in the US, Twitter and Gitter were essential communication channels.

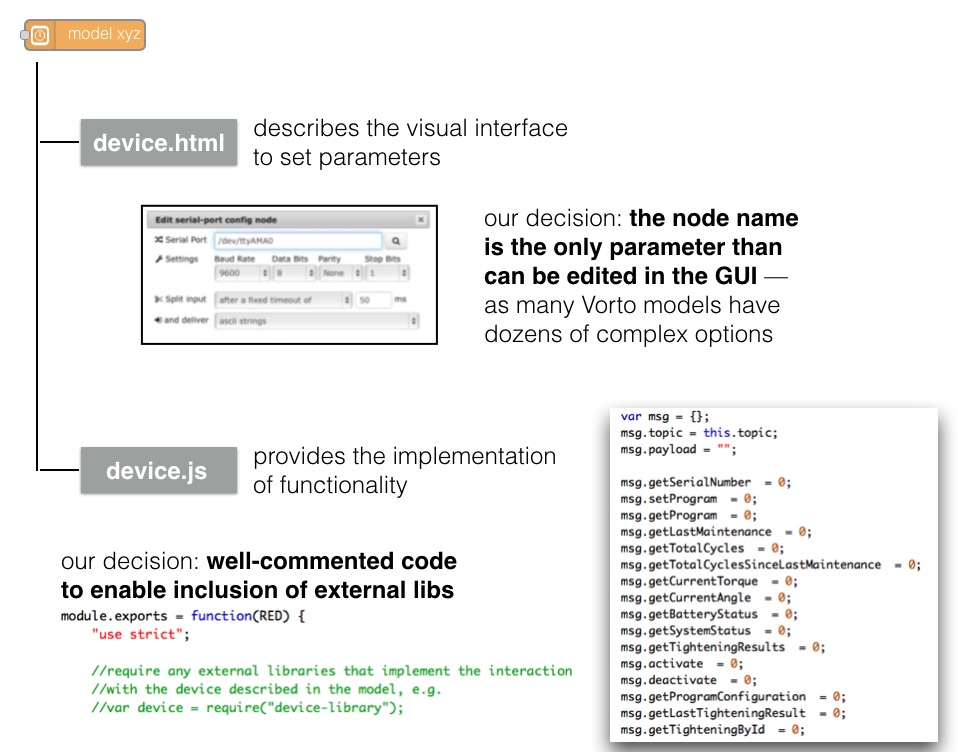

Node-RED nodes are usually composed of two files: an HTML file that defines the look of the node, and a node.js file with the actual implementation. The Node-RED node code that is being generated by our code generator really only defines an interface to the Vorto definition. From the data model itself it is hard to infer which parameters should definitely be presented and which ones are less important. Hence, we opted for a GUI-less representation of the device and only the name of the node can be edited. All properties of the data model are auto-generated in the code and are accessible through the message object msg. At appropriate sections in the code, we highlight where to include external libraries and write the code that ultimately interacts with the hardware.

Node-RED nodes are usually composed of two files: an HTML file that defines the look of the node, and a node.js file with the actual implementation. The Node-RED node code that is being generated by our code generator really only defines an interface to the Vorto definition. From the data model itself it is hard to infer which parameters should definitely be presented and which ones are less important. Hence, we opted for a GUI-less representation of the device and only the name of the node can be edited. All properties of the data model are auto-generated in the code and are accessible through the message object msg. At appropriate sections in the code, we highlight where to include external libraries and write the code that ultimately interacts with the hardware.

As code stubs and header files are entertaining only for the best of geeks, we collaborated with Thomas Amberg who had managed to hack a Bosch Rexroth Nexo Nutrunner industrial screw tightening tool, for which we had a Vorto data model available. It took us indeed only a few minutes to integrate his code into the Node-RED node stub, and allow people to send tweets to the Nexo hand tool.

At the same time, @tamberg writes code to control a beastly industrial nut runner. See projects converge? #bcx16 pic.twitter.com/wKW4Ehjj2t

— Boris Adryan (@BorisAdryan) March 8, 2016